‘No bird soars too high if he soars with his own wings.’ — William Blake

When I lived in London I hated pigeons, they seemed to be just another thing in my way, trying to ambush me in my silence. Now that I live by the sea I spend hours numb with joy watching gulls, oystercatchers and sand martins swooping, diving and dancing through the clouds and waves. Though they are harder to come by here, a pigeon now often sits on the chimney of my stove echoing its coo into my house and I turn my head like a dog each chime that sweeps in, just listening, enjoying and happy to be ambushed amid my silence.

I feel a strange guilt for my time in London being so critical about these birds, especially now that I give so much of my time and awe to their coastal cousins. Weren’t those pigeons just trying to survive too? Doing their best to navigate their lives in grey dust rarely seeing the sun set from the ledges they lived on. Or as Will Self said about the pigeons in Artist Stephen Gill’s book titled PIGEONS “...we see those mythical beings: the young pigeons. I suspect it's because we've entered this otherworldly realm that we find these juveniles to be arousing not of pity, but a grudging respect far from being scroungers, or undeserving poor, these doughty birds survive and even thrive, despite barbs and more barbs of outrageous human fortune.”

What defines a bird's world? And how do they see it? How can they show it to us? Stephen Gill offers us a glimpse of this in his book and “Gill's photographs are devoid of sentiment or affectation rather than showing the pigeon in our world, they take us into theirs. The lens noses in under bridges, squeezes through cracks and scopes out crannies.” says Will Self.

In an article for the New York Times about her quest across cities tracking pigeons as part of her commission for New Museum’s Ideas City, artist Chloé Roubert said “They’re kind of in this limbo zone—pigeons have no use at all, for anything,” she said. “They kind of represent ourselves. What we used to be. We brought them over, now we dislike them, and they’re kind of the mirror of things that we don’t want to deal with.”

The project A Pigeon’s Perspective for Ideas City involved two walks of the Lower East Side of NYC in a pigeon tour. When discussing the project, Roubert said “The presence of pigeons in cities stands on a paradox: they are physically excessively present but remain conceptually invisible.”

But what about a time when pigeons did have a use?

In 1907, Dr Julius Neubronner patented a camera that could be attached to pigeons. Neubronner, an apothecary, had been using pigeons to transport medication and prescriptions with a sanatorium a few miles from his home. A pigeon had become lost during one of these routine flights and to Neubronner’s surprise returned safely 4 weeks later. This prompted the idea to attach a wearable camera to his couriers and have them record their journey’s. A few iterations of the camera had been created until Neubronner settled for a lightweight design that involved a pneumatic shutter which would activate at intervals. The camera had a leather harness and a breastplate and was attached around the body of the pigeon pointing down at the world as they soared above it.

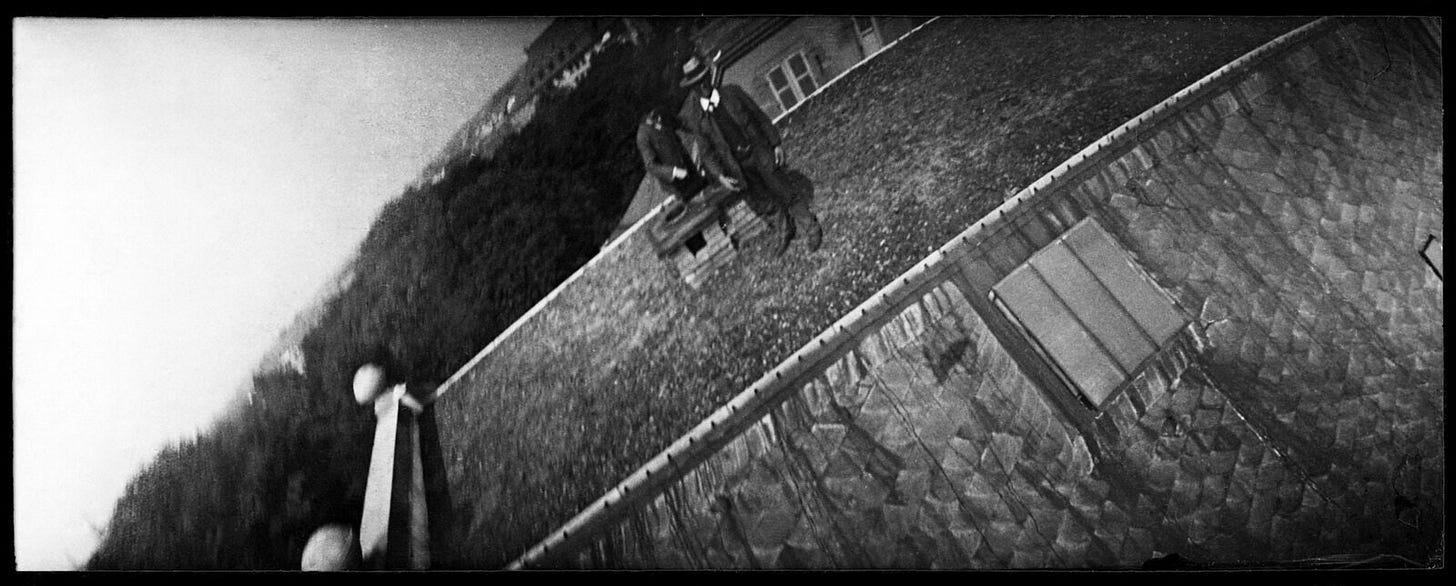

Neubronner had submitted his patent to the German patent office on a number of occasions but kept being rejected. The patent office stated that they felt pigeons could not carry that much weight, Neubronner replied by providing the photographic evidence. These birds could indeed carry the weight and in turn produce unseen perspectives of the world below and of the landscape in which the people who doubted them lived upon. Finally in 1908, Neubronner gained his patent and began to tour these birds and their new found utility, presenting them at expositions across Europe and gained himself notability on an international scale. At an exposition in Dresden, Germany, spectators were able to witness the pigeons return and Neubronner would print the pictures they brought back with them in his makeshift horse drawn darkroom for fans to purchase and take home.

The pictures these pigeons captured showed a world unknown. They offered a perspective of a space merely above our heads and so almost in reach but so impossible to furnish. I find them to be quite moving. They are more than the still image. They go beyond the stillness of an image. And yet somehow they are so perfectly still despite their method of being taken. How even in flight and the frantic pursuit of home we somehow get to see the world stood still and in one single frame. The pictures lift me out of myself and into a place where I only get to see the world from this perspective and with a weightlessness from being untethered. As though for a moment we become the bird.

The image that moves me most is of that very moment we witness the return, as seen below. The joy of coming back, of finding yourself there again even if you weren’t lost. To be heading straight towards a place you call home. It is hard to see a true expression of Dr Neurbronner in this image but his leaning and gaze feel as though he could be about to reach out his arm and extend himself to welcome his loyal carrier home, ready to discover the world it saw on its way back to him.

Pigeons are monogamous, they mate for life. It is this loyalty to family and to love that define the homing pigeon. Their sense of return is a way of life. They don’t just have to come back as part of their task, they want to, they need to. This desire to return has had a profound effect on humans. In the second world war a pigeon named Winkie flew home to its coop in Scotland from the wreckage of the RAF torpedo bomber she had been aboard. The crew had to ditch the aircraft into the sea after being badly damaged during a mission to Norway. The aircrew set Winkie free and she flew home to Scotland in less than 2 hours, flying 120 miles back to her owner who then contacted RAF officials and initiated a rescue mission. Winkie no doubt had no knowledge of her heroic efforts and instead was just happy to be back home with her friend.

Pigeons get a bad rep, but I can’t help but feel like they just want to live with us, alongside us. Aside from their generous appetite, they just want to survive and spend their days with their companions. Somedays I feel like a pigeon. I have this need to return to my life and be with it, my dog, the freshly clean sheets, the cloudless night sky full of stars. I want to return to it and be with it. Cooing into the chimney and ambushing the silence.

Birds make great artists. And as they brush themselves across the sky as though it is their canvas, each flight becomes a new piece instantly installed in the world as an exhibition. Their work is performative and fleeting in its every instant. Never to be seen or done the same again.

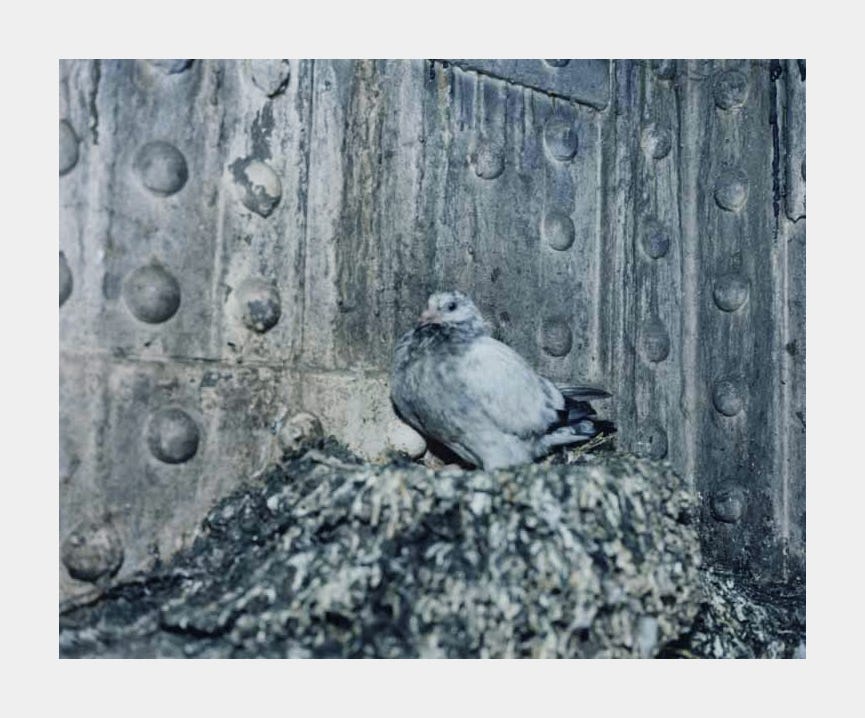

Stephen Gill offers us a view of this in his book The Pillar. I have always been struck by this body of work from Gill. The birds are shown to us in angles and expressions we wouldn’t usually be aware of for the fault of paying little to no attention to them around us. But these birds, they fill the pages of the book and the landscape they roam as their canvas. They fill it with all of their existence, both the stillness and the chaos. And for the first time I feel like I am seeing birds, real birds, birds as they really are.

Where do birds really belong? Are they considered ‘returned’ when they land as they do to this pillar in Gill’s work, back on earth and tethered to it as we humans. Or are they returned in the instant they lift themselves into the sky and do what birds do and fly.

Thinking back to earlier when artist Roubert issued pigeons in New York City as ‘conceptually invisible’ - these birds in Gill’s work are the opposite. They are so conceptually present. The work exists on their presence and how they give themselves to the image simply by arriving, by existing. They are creating something without knowing. Physically present and conceptually visible.

To make the work, Gill installed a wooden pillar in the middle of a field by his home in Sweden and next to that pillar added another that included a camera attached to it. The camera had a motion sensor and would activate and make a picture the moment movement was in view. Gill says he wanted to ‘pull the birds from the sky’.

Similar to those made by Neubronner, these pictures of birds in Gill’s work have a strange paradox of stillness in motion. We see them so evidently in flight, so in life and present in a world that sits still in that instant the shutter closes. And then we see them sitting with that world on the pillar, still and together. Pulled from the sky as Gill intended.

A bird's freedom also somehow holds them captured. Insofar as that the only thing they can do is fly, be free, move between places. In their being free in the world they are able to capture it. It is theirs. I walk past a bird in a cage not far from my house almost every morning. It is placed in the window with a view of the world and all those flying above it. I stop to view it but often find myself with a lump in my throat and asking questions like “does it know that freedom is out here?”... I stumble and want to reach through the glass and open the cage and set it free. But then wonder if the cage is all it knows and its owner is their only constant, their companion. Would I really be setting it free? If the cage is all they know then the cage becomes the world. Does the caged bird know that it can fly? Freedom only exists in the knowledge that you have of it.

A bird can not be defined by its cage. They don’t know beyond its edges or how to build machines that could lift them out of it to help redefine its limits and so they don’t seek it. A bird’s freedom exists in not knowing an end and instead living until it meets one. But meeting an end in the wide open world and living in motion is a freedom I think we would all choose over living and ending in a cage by a closed window wondering if you can fly.

"Hold fast to dreams, for if dreams die, life is a broken-winged bird that cannot fly." — Langston Hughes

See more of the work from Dr Neubronner and his carriers in The Pigeon Photographer, a photobook created by Spanish artist Joan Fontcuberta and published by RORHOF.